Solving 3000 Year Old Crimes

How do you solve a 3,000 year old murder?

A writing project I am planning involves mummies and I thought a fun sub-plot would be for our heroes to find out how they died, essentially solving a 3,000 year old murder. This presents some problems; would it actually be possible? Not solving a murder can make an interesting story, but not as cool as finding out what happened in Ancient Egypt.

The first question is what do I mean by solve? Here's four questions that, if answered properly, would "solve" a murder:

WHO is the victim?

WHO is the murderer?

HOW was the murder committed?

WHY was the murder committed?

(WHY, the motive, is not strictly needed but is probably desirable in a fictional crime. Note that the killer being insane is a perfectly good explanation: see The January Man for example. Similarly the identity of the victim is not required though it is more satisfying, as well as giving detectives some people and places to investigate.)

Ancient Egyptian names would be written in either hieroglyphs (yay!) or hieratic script (boring). The demotic script was not developed until 650 BCE so later than the time period I intend to focus on. Earlier time periods also have sketchier history allowing me to, perhaps, slip more unlikely ideas into the gaps in the record. Stone monuments and objects (also metal and ceramic) exist that have hieroglyphs on; also papyrus from this period still can be read (they have often deteriorated rapidly with handling and transport, and in the damper climate of Europe). These would have to be the sources of the identities. Presumably then they would be royal (or noble, or priestly), which might give a handle on motive.

As for the cause of death, how do we learn such things from mummies without destroying the evidence of such fragile remains? MRI scans or X-rays would be best.

Did I mention that the story is set in 1902?

That still leaves an autopsy. Of course the process of mummification involves removing several organs, like in an autopsy, so the clues might have been erased... or preserved in a canoptic jar.

A final note: just as designing a mystery story with the crime first can lead to our detectives making dubious leaps of intuition to solve it, designing the solution first can lead to a crime that makes no sense at all and relies on several far-fetched coincidences. This is fine in real life, which is full of nonsensical crimes and ridiculous coincidences, but people hope for more coherence from fiction. It is my intention to run through the sequence of events, of both crime and detection, and ask at each stage - is this is a stupid thing for the characters to do? If so, then I need to give them a reason for being such idiots.

A writing project I am planning involves mummies and I thought a fun sub-plot would be for our heroes to find out how they died, essentially solving a 3,000 year old murder. This presents some problems; would it actually be possible? Not solving a murder can make an interesting story, but not as cool as finding out what happened in Ancient Egypt.

The first question is what do I mean by solve? Here's four questions that, if answered properly, would "solve" a murder:

WHO is the victim?

WHO is the murderer?

HOW was the murder committed?

WHY was the murder committed?

(WHY, the motive, is not strictly needed but is probably desirable in a fictional crime. Note that the killer being insane is a perfectly good explanation: see The January Man for example. Similarly the identity of the victim is not required though it is more satisfying, as well as giving detectives some people and places to investigate.)

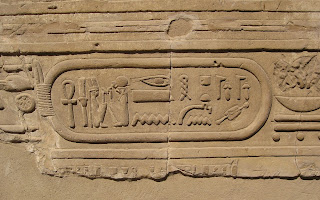

|

| This is probably a name but I don't know whose |

Ancient Egyptian names would be written in either hieroglyphs (yay!) or hieratic script (boring). The demotic script was not developed until 650 BCE so later than the time period I intend to focus on. Earlier time periods also have sketchier history allowing me to, perhaps, slip more unlikely ideas into the gaps in the record. Stone monuments and objects (also metal and ceramic) exist that have hieroglyphs on; also papyrus from this period still can be read (they have often deteriorated rapidly with handling and transport, and in the damper climate of Europe). These would have to be the sources of the identities. Presumably then they would be royal (or noble, or priestly), which might give a handle on motive.

As for the cause of death, how do we learn such things from mummies without destroying the evidence of such fragile remains? MRI scans or X-rays would be best.

Did I mention that the story is set in 1902?

That still leaves an autopsy. Of course the process of mummification involves removing several organs, like in an autopsy, so the clues might have been erased... or preserved in a canoptic jar.

A final note: just as designing a mystery story with the crime first can lead to our detectives making dubious leaps of intuition to solve it, designing the solution first can lead to a crime that makes no sense at all and relies on several far-fetched coincidences. This is fine in real life, which is full of nonsensical crimes and ridiculous coincidences, but people hope for more coherence from fiction. It is my intention to run through the sequence of events, of both crime and detection, and ask at each stage - is this is a stupid thing for the characters to do? If so, then I need to give them a reason for being such idiots.

Comments